These big nursing trends emerged since the Affordable Care Act and our financial crisis which impacted the healthcare industry at every level. Calls for transparency in healthcare billing as well as inter-professional collaboration among doctors, nurses, hospital staff, and insurance providers for the purpose of higher quality care have made healthcare organizations more accountable for their costs. Nurses especially have felt the enduring sting of the financial crisis, and they continue to struggle with high patient-to-nurse ratios, a declining population of nurse educators, and an aging workforce that is likely to retire en masse very soon.

However, such setbacks and liabilities are counterbalanced by the hope of a growing cohort of well-educated, young nurses who are meeting high demands to care for the elderly; an increasing emphasis on holistic and preventive medicine that is empowering nurses in the realm of primary care; as well as a rising tide of technological innovation that is producing new careers for nurses worldwide. The list we’ve compiled below highlights all of these trends and many more that are changing the field of nursing today for the betterment of medicine tomorrow.

1. Entrepreneurs Are Building Better Nursing Homes

Featured Programs

The Great Recession put a strain on elderly care for both patients and healthcare practitioners alike. Entrepreneur Barry Berman took notice when his own parents entered his own nursing home under living and working conditions that left much to be desired. After marked improvements in these conditions over the past 10 years–changes that have resulted in more elderly patients choosing nursing homes that operate under Bill Thomas’s Green House Project business model–there is a demand for certified nursing assistants to work in these facilities. Both patients who currently live and nurses who currently work in Green House Project long-term care facilities report a higher quality of life and higher job satisfaction, respectively.

2. Massive Increase in Online Training

In 2010, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) called on all nurses to increase the percentage of workers holding a BSN from 50 to 80 percent by 2020. Universities have responded by increasing their online course offerings for nursing programs that provide RN to BSN degrees. Programs such as these often coordinate nurses’ clinicals with communities that are local to them, as well as promise higher earnings and job security for career-RNs to help them face increasingly stiff competition brought on by younger nurses with higher educations (see trend 9). Comprehensive lists of on-campus and online nursing programs ranging from RN to BSN, RN to MSN, and Doctor of Nursing Practice (DNP) are available.

3. Emphasis on Art Therapy

Although hospitals (and especially pediatric and psychiatric wards) have always cultivated wide-ranging art exhibits, some hospitals have begun working with culture councils on increasing opportunities for patients, nurses, and volunteers to participate in various arts initiatives. According to research conducted by various reputed institutions that back the American Art Therapy Association, such initiatives improve the physical, mental, and emotional well-being of children and adults worldwide.

Institutions that back the American Art Therapy section include (but are not limited to) the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Nursing, Georgetown University’s Children’s Medical Center, and Johns Hopkins Bayview. See this list for 100 art therapy exercises that nurses can use to engage their patients during downtime.

4. Advocacy for Music Therapy

Veterans, cancer patients, routine surgery patients, and people with Alzheimer’s are all benefiting from nurses who are Board Certified Music Therapists (MT-BC). Studies show music therapy reduces anxiety during routine procedures, decreases the need for inoculative pharmaceuticals, and lessens the likelihood of wandering or elopement. Additionally, the method is known to increase patient positivity, overall satisfaction with life quality, and meaningful interactions with others. Nurses can find the most recent news on outcomes for music therapy and professional development at musictherapy.org.

5. Shortage of Experienced Nurses

Since the year 2000, books have been published about the lack of incoming nurses. Although the Bureau of Labor Statistics recently projected 19% growth in the number of U.S. nurses between 2012 and 2022, the global number of nurses has stagnated. The Great Recession had much to do with this stunted growth, as nurses on the cusp of retirement declined to retire during the economic downturn, keeping what few jobs that workers entering the field had hoped to occupy.

Compound the top-heaviness of an aging workforce (see trend 6) with the low growth rate experienced internationally between 2000 and 2010, and you get a high demand for nurses (and nurse educators) worldwide. Nurses who are soon to retire will need to be replaced, new positions created to serve a growing population, and new faculty hired at nursing schools to meet such imminent demands. Additionally, more incentives are needed for experienced nurses to stay on as educators, because with practicing nurses making $20,000 to $30,000 more than teachers of nursing, the educators of our next generation are dwindling.

6. An Aging Nursing Workforce That is Putting Off Retirement

Peter McMenamin, senior policy fellow and health economist at the American Nurses Association (ANA), had expected 2-3 million more patients to enter Medicare after 2009 based on the assumption that Baby Boomers would begin retiring in 2010. The problem is that most of these Boomers (i.e., nurses who got their jobs in the 1970s and early 1980s) aren’t retiring.

Because of the economic crisis, they have held on to their nursing caps, subsequently slowing and endangering the flow of new blood by creating a bottleneck at the end of the pipeline. This stoppage is being relieved as a new surge of nurses enters the field, urging older nurses to exit their positions. However, these retiring nurses will soon need nurses of their own to care for them as they age, which means a higher demand for geriatric nurses will soon be in order, accompanied by higher job security for those who choose to take care of the old.

7. The Scope of Medicine that Nurses are Able to Practice is Widening

With a shortage of Primary Care Physicians looming, healthcare facilities are beginning to rely more and more heavily on an increase in nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs). Such facilities include hospitals, retail clinics, and nurse-led clinics often based in pharmacies, grocery stores, and other “big box” stores. Studies conducted by members of the Institute for Health Policy Studies and the Medical Industry Leadership Institute have also shown that insurance savings could amount to $810 million if all states allowed NPs to practice independently, and $472 million if NPs were allowed to both practice and prescribe independently, all of which they are trained to do.

While there are longstanding legal and conventional barriers to enacting these practices (e.g., malpractice laws and physicians who feel their territory is being intruded upon), research from various medical, economic, and public health institutions supports the prospect of widening the scope of medicine that nurses are able to practice. There are many excellent public health programs for nurses as well as non-nurses.

8. Steady Growth in the Number of Nurse Practitioners

During the 1990s, nurse practitioners began migrating from hospitals to other sites in their communities to answer a call for accessible care. This move led to a 20% increase in the number of U.S. nurse practitioners between 1992 and 1999 (from 48,000 to 60,000). Since 1999, the number of nurse practitioners has grown to over 205,000. That’s more than a 330% increase in the number of nurse practitioners over a 15-year period (up from a meager 20% increase over an 8-year period), which means that the field has grown at an average rate of 22% per year since 1999.

Over half (54.5%) work in family practice. Approximately 19% work in adult care, 7% in acute care, and 5% in pediatric care. Only 3% work in psychiatric/mental health care, 1% in neonatal care, and 1% in oncology care. With so many NPs going into family practice, healthcare facilities need NPs to distribute themselves throughout other subfields that require more resources. In line with the “Mental Health Crisis” that America is said to have on its hands, there is a current shortage of psychiatrists, which means the subfield of Psychiatric/Mental Health is in more need than most.

9. More Nurses Are More Highly Educated

As RNs strive to meet the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) goal of reaching an 80% BSN-holding workforce by 2020, there has been a marked increase in the number of BSN candidates at on-campus and online universities since 2010. That same year, the IOM called for nursing programs nationwide to double the number of nurses holding doctoral degrees. In response to this demand (which appears to have started even earlier than 2010), the number of universities offering programs for a doctorate of nursing practice (DNP) has grown from twenty in 2006 to two hundred and sixty-four in 2014. That is a 1,320% increase over 8 years.

Studies have also shown that higher numbers of nurses who are more highly educated are also leading to higher quality care. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) cites at least eleven independent studies that found nurses who have a baccalaureate degree or higher are more likely to reduce patient mortality rates and increase overall quality of care. So despite a costly national student loan debt, the higher education of American nurses appears to be paying off for American patients.

10. The Field is Getting More Diverse

Of the 3.5 million employed nurses in 2011, 330,000 were men. That means roughly 1 in 10 nurses were men. Now that sounds like a very small fraction, but when compared with the ratio of male nurses to female nurses in the early 1980s, the field has made definite strides, including a 660% increase in the total number of men working as nurses since 1981. Additionally, the number of male nurses in 2011 who were ethnic minorities (i.e., Non-White) was slightly higher (~5%) than the number of female nurses who were ethnic minorities, a trend that has continued to grow uninhibited for the past 30 years. But with healthcare organizations’ continued focus on recruiting men to the field, the number of men in nursing is sure to increase at a higher rate for the foreseeable future.

11. Gender Pay Gap Closing Steadily

Nursing fits the national mold of having a gender pay gap, otherwise known as the Glass Ceiling. Today, that gap is closing and that ceiling is close to shattering. According to U.S. Census data on the earnings gap in 2000, female nurses made an average of $39,670 while male nurses made an average of $88,217. That’s a $48,547 difference, which translates into female nurses making 45 cents for every dollar made by a male nurse. The good news? That gap closed by 46 cents between 2000 and 2011.

According to U.S. Census data for men in nursing occupations, male nurses earned an average salary of $60,700 per year, while female nurses earned an average salary of $51,100 per year. That’s only a $9,600 difference, which is progress when compared to the almost 50,000 dollar difference only eleven years ago. This progress means that women who worked as nurses in 2011 earned an average of 91 cents for every dollar that men earned–13 cents more than the national average. And with only 9 cents to go toward achieving pay equality for women in the field of nursing, it would appear the hospital’s glass ceiling is cracking.

12. Increased Specialization Among Nurses

RNs who specialize in various areas are in higher demand than generalist LPNs. This demand correlates directly with the growing number of nurses (86.3% between 2007 and 2011) who hold BSN degrees, have received field-specific training, and have been certified to practice in one of several medical subfields (e.g., psychiatry, gerontology, or obstetrics). Following this trend, the number of LPNs hired at hospitals, physicians’ offices, offices of other health practitioners, and residential care facilities (i.e., higher-paying employers that often require more than general care) has declined notably since the year 2000.

The loss of over 10,000 LPNs from the offices of physicians between 2000 and 2010 alone is telling in this regard. Fortunately, LPN jobs are projected to grow by 25% over the next seven years (that’s 6% more than RN jobs are projected to grow), as additional educational opportunities are being made for LPNs to advance into other medical subfields. Regardless of nursing licensure, one thing is certain: nurses today are expected to specialize.

13. A Revised Ethical Code for Nurses

Work environments for nurses are changing rapidly. Families and patients are growing more diverse. Technological advances have led to the presence of more healthcare data being made public. New payment models for health insurance and employee salaries have put pressure on public and private healthcare organizations to find more cost-effective ways to run their facilities. The ANA’s most recent code of ethics has been updated to reflect these changes.

As a revised version of 2001’s Code of Ethics for Nurses, the code focuses on providing patient-centered care like usual, while also making more detailed provisions for advancing the field through scholarly inquiry, research, and the generation of health policy. In particular, the code makes more specific provisions for nurse inclusivity in the public realm, asking nurses to advocate for public health, reduce care disparities among racial and ethnic minorities, and apply the principles of social justice throughout the medical field. These revised provisions set the stage for 2015 as the “Year of Ethics,” and they promise to serve as guiding principles for nurses in the years to come.

14. Nurses Pushing for Inclusion on Hospital Boards

Although nurses take active leadership roles in hospitals throughout the U.S., they are underrepresented on hospital boards. Since a 2011 survey found that only 6% of board members in 1000 hospitals were nurses (meanwhile 20% were physicians) there has been a push toward including nurses in the boardroom. As part of this push, a national coalition of organizations, including the American Nurses Association (ANA), the American Academy of Nursing (AAN), and the American Nurses Foundation (ANF) among 18 other nationally-recognized organizations, has been formed to create the Nurses on Boards Coalition.

The organization seeks to implement a comprehensive strategy that will “bring nurses’ valuable perspective to governing boards, as well as state-level and national commissions.” With big players like AARP and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation backing this initiative, it is likely their recommendation that nurses play bigger roles in “improving the health of all Americans” will see more nurses becoming movers and shakers not only in their field but also in hospitals as a whole.

15. Increased Focus on Preventive Medicine & Holistic Care

Health care reform initiatives begun by the Affordable Care Act in 2010 and instituted worldwide before then have resulted in the growing demand for nurses who provide preventive and holistic services. Nurses’ clinical skill-sets, bedside manner, and training in patient instruction make them ideal candidates for providing the level of care and leadership necessary to manage these procedures. With the shortage of PCPs and psychiatrists (see trends 7 and 8), healthcare organizations will be relying more and more heavily on nurse practitioners (NPs) for both chronic and family care. Once NPs become empowered to prescribe, conduct screenings, and educate patients, it won’t be long before “an apple a day keeps the doctor away,” gives way to the nurse.

16. Rise of Awareness for Compassion Fatigue

Since the mid-1990s, nurses have become aware that it is possible to care too much for too long. Compassion fatigue is a chronic stress condition that also goes by the name of Secondary Traumatic Stress. A consequence of either one-time or repeated exposure to trauma as well as those who experience trauma directly, common symptoms include excessive blaming, bottled up emotions, isolation, poor self-care, flashbacks to traumatic events, chronic physical ailments (e.g., gastrointestinal problems or recurrent colds), apathy, denial, and mental and physical exhaustion.

Caregivers now recognize that compassion fatigue can also manifest itself at the organizational level in the form of high absenteeism, lack of collaboration among team members, inability to meet deadlines, negative attitudes toward management, strong reluctance to change, and a lack of vision for the future. Both individuals and organizations are taking a “path to wellness” by screening themselves for symptoms. Additionally, more and more nurses are getting certified in Compassion Fatigue Education to meet the needs of those suffering from the condition.

17. Nursing School Faculty Shortages

As recently as 2014, nursing faculty were making about $20,000-$30,000 less than practicing nurses. Pay gaps such as these have led to more nurses practicing instead of teaching. Pair this gap with the fact that a large cohort of nurses is about to retire, and Deans of Nursing such as Kathryn Grams are saying that “Nursing education is in crisis.” In fact, many nursing programs at community colleges are losing accreditation because their number of qualified faculty has dropped so severely.

With an average age of 60 for nursing professors who hold doctoral degrees and so many graduates with BSNs and MSNs going into careers that provide higher-paying salaries at hospitals, corporations, and the military, the latest hope for nurses learning the trade is that they will stay on and educate the next generation. And as more nurses get their BSN and more DNP programs arise (see trend 9), nurses can expect to be given more incentives to do just that.

18. Increased Focus on “Collaborative Healthcare”

Collaborative healthcare rose to popularity after the Affordable Care Act made way for Medicaid health homes. Its holistic method combines primary, acute, behavioral, and long-term services for a comprehensive approach to providing for the whole person in one place as opposed to treating special conditions at multiple locations. Designed to care for those with serious or chronic physical and mental health issues, 28 health homes have started up in 19 states by healthcare entrepreneurs such as Dr. Amy Boutwell. These entrepreneurs need nurses of all qualifications to staff homes at all levels of their collaborative care teams. 70 such teams have been studied over the past 15 years. Across all fronts– primary, acute, behavioral, and long-term–collaborative care has consistently demonstrated higher effectiveness than usual care.

19. Nurses Need Technological Expertise More than Ever

Numerous Studies, reports, and surveys attest that information technology has increased patient satisfaction, reduced clinical errors, and decreased the amount of paperwork for nurses to perform outside the room. Today, nurses use a variety of data-driven approaches to perform their job in the room, including Electronic Health Records (EHR) for tracking patient and family health histories, Smart Beds for obtaining patients’ vitals, and Point-Of-Care Technology to access patient case records before conducting special procedures such as X-rays. This new focus on data-gathering with the patient has been called Nursing Informatics or NI, and it is quickly growing into its own, as nurses interested in data science and communication technology are in high demand for new jobs that will help develop this new field for nursing worldwide.

20. Rise in Geriatric and Palliative Care as America Ages

According to the Congressional Budget Office, 20% of the U.S. population will be 65 or older by 2050, a 12% increase from 2000 when only 8% of the population was 65 or older. Only 1% of nurses are currently certified in geriatrics, despite over half of those admitted to hospitals being over the age of 65. This means 1% of nurses are caring for over 50% of the United States’ hospitalized population. In other words, approximately 35,000 nurses are caring for over 17 million patients, with roughly 1 geriatric nurse for every 486 geriatric patients. As the U.S. continues to age, this gap will only widen unless a cohort of young nurses steps in to care for the elderly. With job outlooks “Excellent” for Geriatric Staff Nurses right now, the time is ripe to get certified in Geriatric Care Management, and to continue building better nursing homes (see trend 1).

21. Increased Focus on Patient Safety

Since the financial crisis, many hospitals have refused to invest in assistive technologies that would improve patient safety and protect nurses from injury. Nurses began to protest. Citing hospital corporatization as their raison d’etre and picketing with signs that support “Patients Before Profits,” nurses all over the world have joined the chorus of healthcare professionals calling for patient safety. Their hard work has paid off. As of 2013, new Patient Safety Goals have been distributed to hospitals throughout the United States. They have also been made available to international healthcare organizations online, placing emphasis on the nurse’s role in campaigning for these changes.

22. Worsening Physical Conditions Are Decreasing Nurse Job Satisfaction

A decline in nurses’ physical working conditions is correlated with the patient safety movement mentioned above. The more nurses who suffer on-the-job injuries due to poor physical working conditions, the fewer patients can be cared for and kept safe from further harm. ANA president, Karen Daley, cites the Bureau of Labor Statistics finding that musculoskeletal injuries suffered while moving patients from one room to another are the number one reason nurses are forced to either take time off or leave the bedside altogether. In fact, nursing assistants topped the list of occupations with musculoskeletal-related disorders, beating out manual laborers, janitors, and truck drivers with the highest number of on-the-job injuries.

Nurses have responded by calling for more lift-technology in their healthcare facilities. Additionally, studies conducted by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation have concluded that enhancing nurses’ physical working conditions with new technology decreases the likelihood of on-the-job injuries, increases efficiency with architectural layouts that are aesthetically pleasing, as well as improves inter-professional communication with interior design that makes employees and patients comfortable all lead to a marked lift in overall job satisfaction among nurses and physicians.

23. Nurses Taking Charge of Patient Education

Nurses have taken on the role of patient-educator since the profession’s infancy. Dorothea Orem, the nurse famous for having developed the Self-Care Theory over the course of the twentieth century, instructs her peers that the goal of nursing is to render the patient capable of caring for him or herself. Nurses today follow this model by informing patients about procedures, their prescriptions, and symptom management often without even knowing they are doing so. However, more and more recently, nurses have been noticing that the incorporation of patient education and health literacy leads to more optimal patient outcomes. Such outcomes have inspired a spike in the number of resources available for teaching health literacy, allowing nurses to arm their patients with knowledge today so that they can care for themselves tomorrow.

24. Nurses Called Upon to Play Role in Health Informatics

Health informatics is a growing specialization in the healthcare profession that uses electronic health records, health information exchange technology, and portable medical data collection platforms to foster collaboration between patients, nurses, physicians, and other various healthcare providers. With the demand for informatics in the medical workplace seeming to increase daily, new positions have been created to collect patient data.

These new positions include nurse informaticists (see trend 19 for more information on growth potential and average salary), who are responsible for selecting and evaluating new technologies, collecting data, analyzing trends, and making recommendations for implementation to stakeholders. As information technology continues to play an increasingly large role in the medical field and nurses get their foot in the door of hospital boardrooms (see trend 14), the call for nurses who can use data to care not only for patients but also for their organizations will need to be answered. Do you have what it takes?

25. Call for Transparency and Accountability in Healthcare Billing

The Affordable Care Act called for an increase in the degree of transparency that healthcare organizations show patients when it comes down to brass tax. This call for transparency has trickled down to affect the way nurses and physicians do business, as patients are coming to their appointments looking for a concrete price tag. Today, nurses can expect to hear those three dirty words associated more often with business transactions than getting surgery: “What’s the cost?” Nurses should prepare themselves for questions like this by familiarizing themselves with the basic costs associated with the treatments and procedures they provide, especially because those costs are becoming publicly accessible.

26. New Outcome-Based Models for Billing and Measuring Success

After more than two dozen former therapists, rehabilitation specialists and other healthcare professionals at specialized nursing facilities (SNFs) admitted to pressuring nurses to meet quotas in order to receive Medicare benefits, medical insurance companies are exchanging pay policies based on output for pay policies based on outcomes. In other words, special nursing facilities are finding themselves working to achieve value instead of volume.

This move toward increasing the quality of care and managing outcomes in SNFs is nothing new to U.S. nurses, who, after the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, we’re expected to adopt an outcome-based, value-based economic model for billing and measuring successful care. Nurses have responded by developing research fields like Nursing Informatics (see trend 24), which aid in the measurement of patient outcomes. And with billing becoming more transparent (see trend 25), it’s only a matter of time before nurses are considered primary sources for measuring the success of their healthcare organizations.

27. The Rise of Retail Clinics

Urgent Care, Pharmaceutical, and Nurse Practitioner-led clinics rose from 150 to nearly 700 between 2008 and 2011. With up to 90 percent of retail clinic patients walking in for on-the-spot treatment at Walgreens, CVS, and Wal-Mart, acute care has become more consumer-driven than other types of care. Nurse practitioners are capitalizing on this move by opening up their own clinics, treating families, and essentially operating as private practices within retail locations. If projections for the decline in primary care physicians are correct (see trend 7), then the U.S. is going to be short 45,000 PCPs by the year 2020. That means the growing market for startup clinics is not only good for business but also for community health as a whole.

28. Rethinking Nursing Care for Dementia

In 2009, the Alzheimer’s Association released its Campaign for Quality Residential Care, recommending further measures be taken toward engaging patients socially while also respecting their individual boundaries. Traditionally, patients with dementia have transitioned rather abruptly and with much consensual difficulty from family and long-term caregivers to end-of-life preparation. But a study published in 2012 found that nurses can play expanding roles in smoothing this oftentimes lengthy transition.

These roles include nurse educators to help family members understand what their loved one is going through (see trend 23), as well as nurse assistants to provide anticipatory guidance to family caregivers who are treating patients with dementia. There is also a call for gerontological nurse instructors not only to educate their students but also to update their senior peers about the ever-growing body of research on the disease’s progression. Nurse informaticists (see trend 24) with specializations in gerontology would be ideal candidates for contributing to this body of research and aiding the medical field in its mission to understand and rethink the way we treat this disease.

29. Spiritual Care and Nursing

The principles of spiritual care are based on compassion, the root of which means “to suffer for.” Arising out of a feeling that the cure-driven, technological advances made over the course of the 20th century needed to be balanced with a desire to care for the individual, spiritual care’s role in health care are to tend to the whole person: mind, body, and soul. Nurses have often filled this role in their capacity as caregivers (instead of “cure-givers”) at privately run, religiously affiliated hospitals.

Studies have shown that such approaches are successful in bringing hopefulness to patients, as well as improving their relations with other patients, family members, and their caregivers. Hospital religious affiliation notwithstanding, nurses continue to fill this role today by recognizing and practicing respect for the diversity of religious and spiritual worldviews their patients are likely to maintain. Indeed, nursing leaders recently have seen success in the implementation of spiritual principles by practicing mindfulness meditation with their patients to both manage and relieve stress.

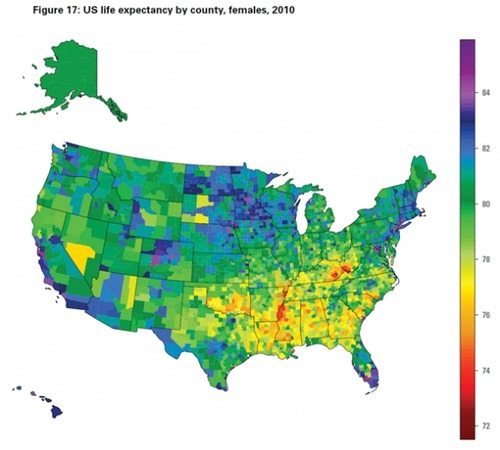

30. Increasing Disparity in Women’s Care Between States

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have noted significant racial and ethnic disparities in women’s health in studies as old as 2005. As recently as 2009, healthcare disparities among women were pinned down on a state-by-state basis, as studies conducted by the Kaiser Family Foundation concluded that thirteen out of fifty states had worse than average health statuses. Those states were confined to the South, the Midwest, and the Mountains and Plains regions, where most healthcare facilities are located in rural areas. Most recently in 2014, the National Women’s Law Center analyzed new sets of data to determine the coverage gap between low-income women without health insurance and women with health insurance in all 50 states.

The coverage gap was staggering between states who had expanded Medicaid and those that had not: women in states with Medicaid expansion were 2 times more likely to get the care they needed than women in states without Medicaid expansion. In a field still dominated by women, nurses in states without Medicaid expansion can combat this coverage gap by urging their legislatures to accept federal aid so that nurses can extend their helping hands to those who need them most.