Understanding the Duty of Nursing Professionals in the Face of a Global Crisis

Pandemic nursing duties are discussed below since many health care professionals may be facing pandemic conditions for the first time. Facilities literally had to rewrite the book when it comes to proper care for those with COVID-19. A shortage of essential supplies has only exacerbated this situation. Nurses on the front lines of health care facilities must decide how to provide quality health care without putting themselves at risk. The Code of Ethics for Nurses with Interpretive Statements guides nurses on how to care for patients safely during crises.

Nurses’ Obligations in a Pandemic or Disaster

Nurses’ obligations in a pandemic or disaster start with knowing and looking out for their own rights. Administrators, managers, and health care providers need to understand their employer’s expectations. This can also make it easier for nurses to confidently volunteer for conditions that make them go above and beyond the call of duty.

When Should Nurses Decline to Treat?

Featured Programs

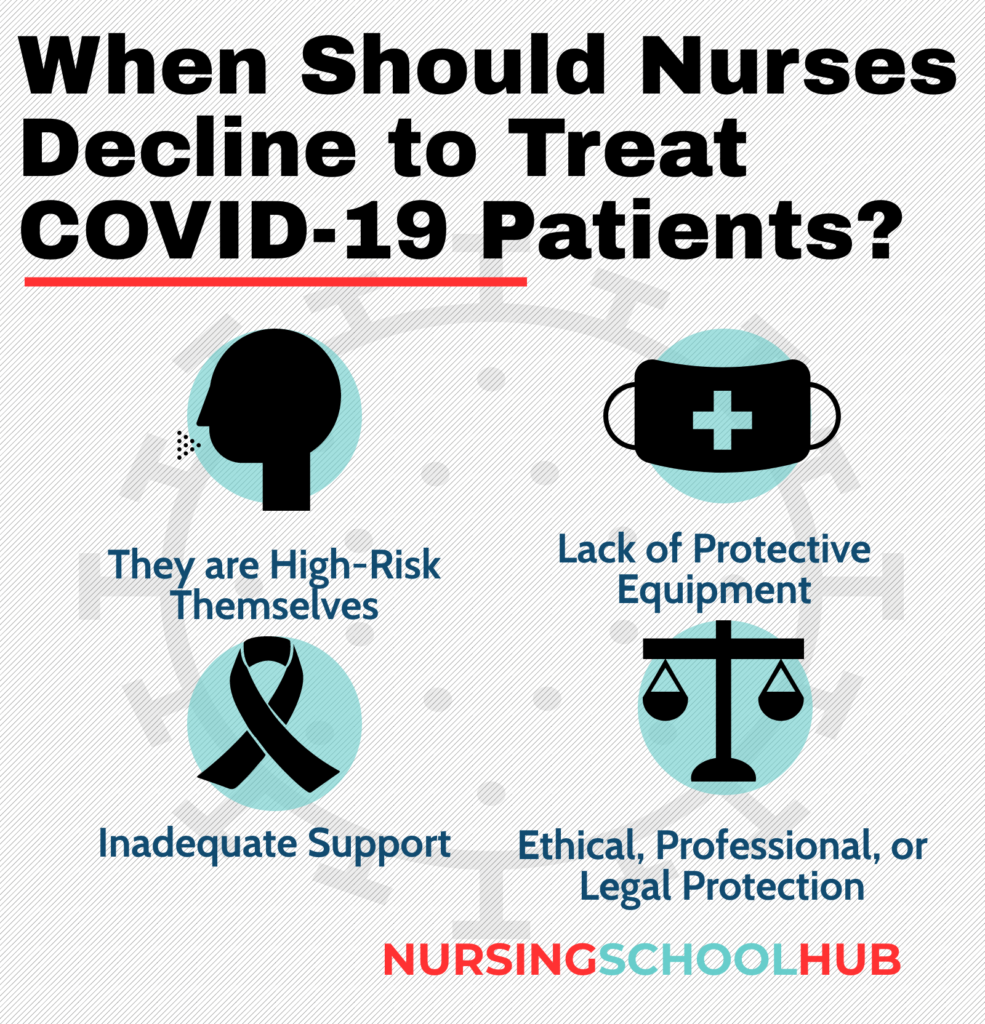

Nurses may choose not to respond in the following circumstances:

- They are in a high-risk group

- They feel unsafe due to a lack of protective equipment or testing

- Inadequate support

- Concern over ethical, professional, and legal protection

Effective communication between nurses and management is essential in order to establish a safe working environment, and the COE notes that nurses should not face retaliation if they raise concerns.

Ethical Treatment of Coronavirus Patients

The provisions in the COE indicate that nurses should treat patients with dignity and respect. The primary commitment is to the patient, whether that is a person, family or community. In this role, the nurse acts as an advocate for the health and safety of the patient.

While emphasizing nurses’ authority and accountability, the COE also stresses that nurses, like all health care workers, owe the same duty of care to themselves. This is crucial in the case of a pandemic where nurses must do all they can to protect themselves as well as their patients. Protective masks, gloves, and clothing are often part and parcel of treating infectious diseases. Nurses should speak up if they see anything that puts themselves, coworkers, or patients at risk.

What Is the Coronavirus and How Does it Spread?

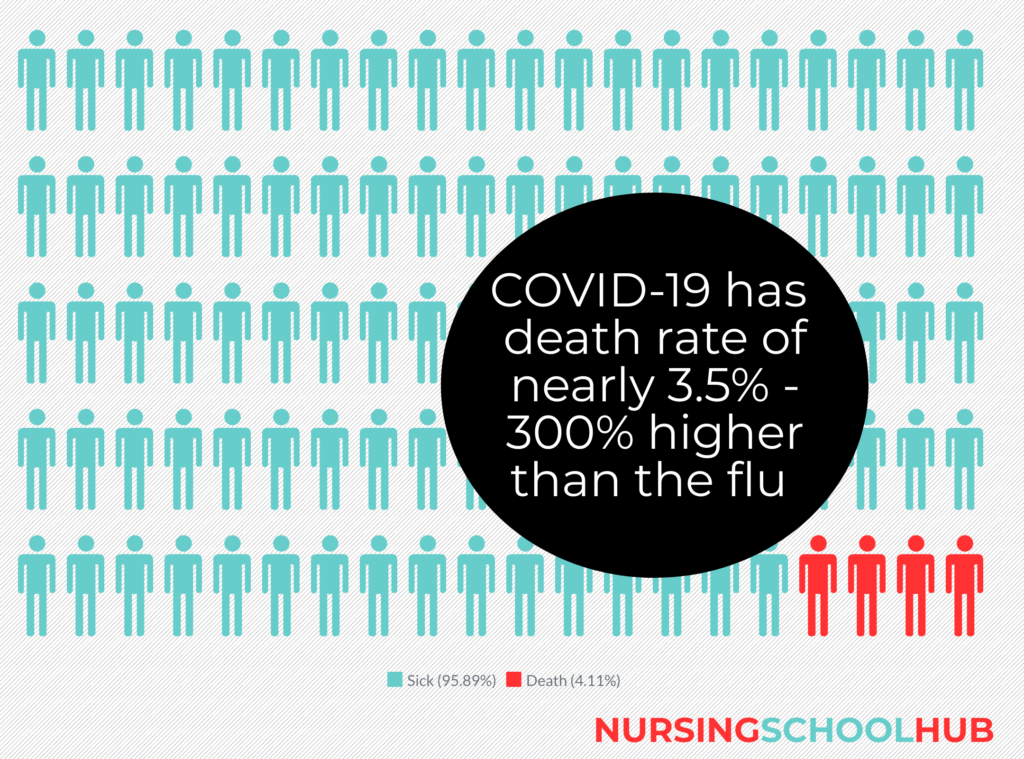

A coronavirus infects your sinuses, nose, and upper throat. Coronaviruses in general are quite common, and most people become ill from it by way of the common cold and similar illnesses. The novel coronavirus associated with the pandemic, also called COVID-19, is a new version that has very severe symptoms for many people, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

The novel coronavirus spreads from person to person. If you come within 6 feet of someone with COVID-19, you run the risk of catching it. When an infected person talks, sneezes, or coughs, respiratory droplets enter the air. If you touch an object or surface with surviving viruses on it and then touch your nose, eyes, or mouth, it can enter your body and make you sick.

Why Is There a Shortage of Coronavirus Tests?

NPR attributes the dearth of coronavirus tests to special swabs used to collect the samples. Called nasopharyngeal swabs, they are not your average Q-tip. As the demand for accurate testing for coronavirus continues, the need for the swabs has become a bottleneck.

Why is there a shortage of coronavirus tests? The lab test for coronavirus relies on these long, skinny swabs that allow medical professionals to reach through the nose into the nasopharynx, which is the upper part of the throat. They consist of synthetic fiber instead of a wooden shaft. Regular wound care swab tips contain calcium alginate, which kills the coronavirus, making them unsuitable for testing for coronavirus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The U.S. and Italian governments are working with companies to ramp up the production of nasopharynx swabs needed for the lab test for coronavirus.

Requirements to Protect and Advocate for Patients

Nurses are often vocal advocates for the health and welfare of patients. The Code of Ethics lists criteria for how to allocate scarce resources. The shortage of respirators in New York City early in the pandemic could be considered one example of critical resources that need to be shared. Some health care workers worried that there would not be enough to go around.

In various contexts, such as triage situations, allocations for ventilators and other equipment should take into account:

- The urgency of medical needs

- Likelihood of benefit

- Duration of benefit

- Change in patient’s quality of life

To decide where to allocate ventilators, nurses and other health care workers may award first priority to those who need the treatment to avoid death and other undesirable outcomes. When no clear differences exist, a transparent and objective decision may be needed. Nurses might not be responsible for such decisions but can provide relevant observations and information to those who are. Patients and their families have the right to know about allocation policies and limited resources that may result in bad outcomes.

Requirements for Safe Working Conditions for Nurses

For nurses involved in treatment for coronavirus, many other questions arise regarding safe working conditions. If you are already a nurse, this is probably something that has come into your mind many times. For instance, what if you don’t feel comfortable with the distribution of personal protective equipment (PPEs) in your facility. Although ongoing shortages may prevent institutions from providing this equipment, what is your obligation to continue to perform services if you feel the protection is inadequate?

This is just one decision among many nurses’ ethical considerations in a pandemic. The urgency of need might include the degree of contact with COVID-19 patients as well as the role of the health care provider. For instance, doctors may be able to diagnose patients without physical contact, whereas a CNA or nurse might have to physically touch the patient to fulfill their obligations. These uncomfortable decisions have no doubt made more than one policymaker cringe already.

Allocating PPE to Health Care Providers

The COE touches on prioritizing available resources to physicians, nurses, and other health care professionals. It makes the argument that those on the front lines hold a high value in the current landscape. Without them, no one else can receive the care they need to live. Therefore, those working in triage situations might have a greater need and claim for personal protective gear. This might also apply to those working in isolation wards full of COVID-19 patients.

Case Study

Prior to the current pandemic, the AMA’s Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs released a 2010 report on immunizations. It details a physicians’ duty to take immunization or medication when they are exposed to harm. The report states the more virulent the disease and the more risk to health care workers, the more obligation nurses and other professionals have to protect themselves.

Second-order risks refer to the likelihood that an infected nurse or other medical professional will give the illness to someone else. This includes patients, colleagues, friends, and family members that come into contact with the health care provider.

Can Nurses Decline to Provide Treatment for Coronavirus?

This is probably one of the toughest questions that nurses, physicians, and other health care workers can ask one another. No matter how many policies and procedures managers write and pass around, subject factors always come into play. How confident do you feel that your treatment of coronavirus won’t endanger yourself or those you love.

Ultimately this is an individual decision. When can you ethically decline to provide treatment for coronavirus if you feel the PPE does not provide appropriate protection against infections? Also, there may be a great deal of pressure from administrators and managers attempting to provide a high level of care with dwindling supplies. What do you do if you disagree with their workarounds?

Whether physicians and nurses might refuse to provide care on ethical grounds depends on many factors. This includes the level of risk and how much direct contact you would have with the COVID-19 patient. For example, you may have an underlying health risk that puts you at greater risk, such as:

- Chronic lung disease

- Diabetes

- Serious heart conditions

- Chronic kidney disease/dialysis

- Asthma

- People 65 years and older

- Severe obesity

- People in long-term care facilities

- Liver disease

- Immunocompromised

If you are over 65, have diabetes and are severely obese, you might want to think twice before stepping into a room without new, clean protective wear.

Unfortunately, there may be facilities that do not have enough protective wear. In this case, managers should find a way to reduce the risk to nurses, aides, and other medical professionals to make the decision easier.

Dealing with Stress

For nurses working with coronavirus patients, it may be impossible to leave the stress at work. Try to find ways to relax at home and be sure to get enough sleep. Diet and exercise play an important role in maintaining a healthy immune system. Whether it’s practicing yoga or doing sit-ups, exercise is a great stress buster.

It’s hard to take care of other people if you aren’t looking out for your own good health.

Nursing and COVID-19 Resources: