The placebo effect infographic summarizes the patient-perceived feeling of taking medicine that is not real.

Share this infographic on your site!

The Placebo Effect: Patient, Heal Thyself

Featured Programs

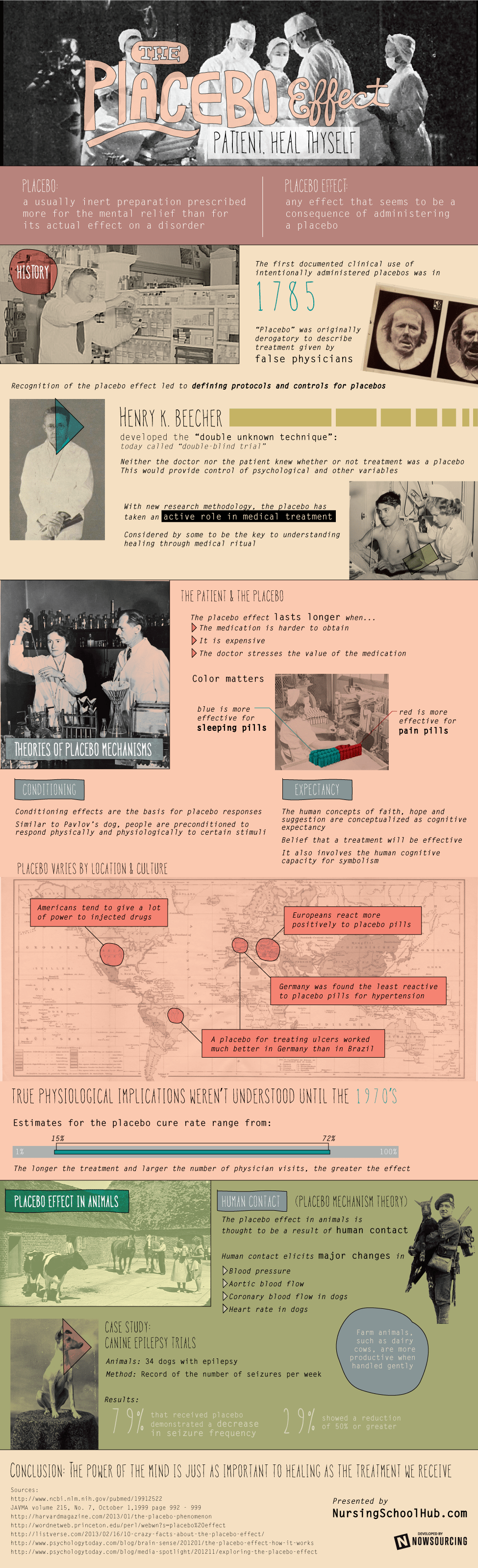

Placebo: a usually inert preparation prescribed more for the mental relief than for its actual effect on a disorder

Placebo Effect: any effect that seems to be a consequence of administering a placebo

History

- The first documented clinical use of intentionally administered placebos was in 1785.

- “Placebo”was originally derogatory to describe treatment given by false physicians.

- Recognition of the placebo effect led to defining protocols and controls for placebos.

- Beecher developed the “double unknown technique” today called the “double-blind trial”

- neither the doctor nor the patient knew whether or not treatment was a placebo, this would provide control of psychological and other variables.

- With new research methodology, the placebo has taken an active role in medical treatment,

- considered by some to be the key to understanding healing through medical rituals.

- Theories of Placebo Mechanisms

Conditioning

- Conditioning effects are the basis for placebo responses. Similar to Pavlov’s dog, people are preconditioned to respond physically and physiologically to certain stimuli.

Expectancy

- The human concepts of faith, hope, and suggestion are conceptualized as cognitive expectancy

- belief that a treatment will be effective. It also involves the human cognitive capacity for symbolism.

- The Patient and the Placebo

The placebo effect lasts longer when

- The medication is harder to obtain.

- It is expensive.

Color matters

- The dr. stresses the value of the medication.

- Blue is more effective for sleeping pills.

- Red is more effective for pain pills.

- Patients who take placebos regularly do better than those who don’t follow a schedule, regardless of the fact that placebos have no real health benefit.

- One study shows people with high dopamine levels are more likely to experience placebo effects.

- The placebo effect varies from disease to disease.

- Subjective ratings of pain, depression, etc. cannot be directly compared.

- It cannot be linked to a particular physical process at work in the body.

- The placebo effect is often vulnerable to psychological factors such as stress and anxiety.

It varies by location and culture

- Americans tend to give a lot of power to injected drugs.

- Europeans react more positively to placebo pills.

- A placebo

- for treating ulcers worked much better in Germany than Brazil.

- Germany was found the least reactive to placebo pills for hypertension.

- It still occurs when patients know they are taking a placebo.

- The power of the placebo has increased over the years.

- The increased power is thought to be a result of social conditioning.

- True physiological implications weren’t understood until the 1970s, researchers studying dental patients found that they could block the placebo effect by chemically blocking the release of endorphins (the brain’s pain killers). This suggested that placebo treatments produce chemical responses.

- Responders to placebos are found to have more endorphins in their spinal fluid.

- Estimates for the placebo cure rate range from 15% to 72%. The longer the treatment period and the larger the number of physician visits; the greater the effect.

The Placebo Effect in Animals

- Placebo Mechanism Theory

- Human Contact

- The placebo effect in animals is thought to be a result of human contact.

- Numerous studies have documented physiological and health effects resulting from visual and tactile contact from a human.

- Human contact elicits major changes in: blood pressure, aortic blood flow, coronary blood flow, and heart rate in dogs.

- Farm animals, such as dairy cows, are more productive when handled gently.

- Increased reproductive efficiency in sows is associated with human presence.

- Case Study: Canine Epilepsy Trials

- Animals: 34 dogs with epilepsy

- Method: Record the number of seizures per week.

- Results:

- 79% that received a placebo demonstrated a decrease in seizure frequency.

- 29% showed a reduction of 50% or greater.

- Another study was done on dogs with arthritis.

- some were given medication and some were given a placebo.

- 56% of the placebo-treated dogs showed a significant positive response. Conclusion: The power of the mind is just as important to healing as the treatment we receive.

Is Faith just the placebo effect in disguise?

- Faith and Healing:

- Faith is unique to human beings and spans all borders of human experience.

- The frontal lobe helps us focus attention in prayer and meditation.

- The parietal lobe controls sensory information; it is involved in the feeling of becoming part of something greater than oneself.

- The limbic system regulates emotions: responsible for feelings of awe and joy.

- Brain scans may provide proof that our brains are built to believe in a higher power (According to author and scientist, Dr. Andrew Newberg).

- Religion has helped humans survive, adapt, and evolve.

- Scientific images can track our thoughts on God, but cannot identify why we think of God in the first place.

- Randomized blind trial of intercessory prayer added to normal cancer treatment:

- Patients completed QOL (Quality of Life) and spiritual well-being scale at the beginning, and 6 months later.

- Participants remained blinded to randomization (they didn’t know if they were being prayed for or not).

- Subjects: 1000 patients with cancer

- 66.6% provided follow-up data.

- Average age: 61 years.

- Most were married or living with partners.

- Most were Christian.

- An external group offering Christian intercessory prayer was asked to add some participants to their usual prayers lists.

- They received details about participants but not sufficient to identify them.

- Results:

- Participants receiving intercessory prayer showed significantly greater improvement in:

- spiritual well-being

- emotional well-being

- functional well-being

- Study on the use of prayer for healing

- Purpose: determine the prevalence and patterns of the use of prayer for health concerns.

- Method: A national survey.

- Data was collected on:

- sociodemographics

- use of conventional medicine

- use of alternative medical therapies

- Results:

- 35% used prayer for health concerns.

- 75% of these prayed for wellness.

- 22% prayed for specific medical conditions.

- 69% of these found prayer very helpful.

- Conclusions:

- An estimated ⅓ of adults used prayer for health concerns.

- The users reported high levels of perceived helpfulness.

- Study of the demographics for those using prayer

- Purpose: Describe the demographics, health-related behaviors, health status and health care charges of adults who pray or do not pray for health.

- Method: Cross-sectional survey with 1-year follow-up.

- Survey included health risks, health practices, use of preventive care, use of alternative therapies, and satisfaction with care.

- Subjects: random sample of 5107 people age 40+ in MN.

- Results:

- 47.2% reported praying for health.

- 90.3% of these believed prayer improved their health.

- Those who pray had:

- Significantly less smoking and alcohol use

- More preventive care visits

- Vegetable intake

- satisfaction with care

- social support

- Rates of functional impairment, depression, chronic diseases and total health were not related to prayer.

- Conclusions:

- Those who pray had more favorable health-related behaviors.

- Discussion of prayer could help guide customization of clinical care. Sources:

http://lib.bioinfo.pl/meid:238314

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22894887

http://www.cnn.com/2007/HEALTH/04/04/neurotheology/ Research: Placebo effect – any effect that seems to be a consequence of administering a placebo; the change is usually beneficial and is assumed to result from the person’s faith in the treatment or preconceptions about what the experimental drug was supposed to do; pharmacologists were the first to talk about placebo effects but now the idea has been generalized to many situations having nothing to do with drugs.

-

- For many years, the placebo effect was considered to be a nuisance effect that needed to be controlled in clinical trials,” Dr. Novella stated. “More recently, the placebo effect has been redefined as the key to understanding the healing that arises from the medical ritual in the context of the patient \ provider relationship and the power of imagination, trust and hope.” Should medical doctors rely on deception to avoid using potentially more dangerous medications? And how effective or reliable is the placebo effect anyway? Dr. Novella pointed out that advocates of alternative medicine have begun using the placebo effect as a way of marketing their products by stressing that the mind can heal the body in way that medical science cannot understand. The more expensive the placebo, the longer the placebo effect lasts for patients. Color of the pill can be important too. For whatever reason, blue sleeping pills are more likely to benefit patients than pills of another color. Medications to reduce pain are often sold in red pills or capsules since marketing studies showed these to be more effective, etc. Patients who take placebos regularly do better than patients who are not compliant with their treatment, regardless of the fact that placebos have no real health benefit. When placebo medications are hard to obtain, more expensive, or otherwise stressed to be valuable to the patient, the placebo effect becomes even stronger. “Physicians are very much aware of the fact that we examine patients, we touch them, and that in and of itself has a physical effect,” Dr. Novella continued. “Being touched in a safe context relaxes and reassures the patient.” There are also non-specific effects in making patients the center of attention. Bringing them into the doctor’s office and asking questions about their symptoms can make them feel as if they are part of the medical team dealing with the health problem. Different non-specific effects can all contribute to what is regarded as the placebo effect. For “fuzzy” symptoms such as chronic pain, patients are often able to convince themselves that placebos are as effective as actual pain medications. Although the human body continues actual physiological mechanisms to control pain, such as generating endorphins, this is not as reliable as actual pain medication. Intriguingly, Dr. Novella also described a recent study showing that people with high dopamine levels in the brain are more likely to experience placebo effects. Although this result only applies to pain and has still not been replicated, the study does suggest that there is a genetic factor that might be at work with the placebo effect And the placebo effect varies from disease to disease. Since subjective ratings of pain, depression, or any other symptom being measured cannot be directly compared. It also means that the placebo effect cannot be linked to any particular physical process at work in the body. Most diseases where a placebo effect has been observed, such as pain, asthma, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), are also especially vulnerable to psychological factors like stress and anxiety. But even when psychological effects are taken into consideration, the evidence that the placebo effect is actually working seems limited. Whatever relief the placebo provides is usually short-lived and the benefit is purely psychological, not physiological. There is also the ethical question surrounding placebos. Are medical doctors ethically permitted to deceive patients into believing they are receiving actual treatment instead of a placebo? Even if the medical doctor believes that the patient will benefit? Actually, Dr. Novella argues that deception is not always necessary and some placebo studies with IBS patients showed that placebo effects still relieved symptoms even when the patient knew about the placebo (though this result is controversial). The real controversy surrounding placebos deals with what the placebo effect actually is and what yjis means about the human capacity for self-healing. While alternative medicine advocates use the placebo effect as evidence that the brain has the ability to heal physical illness in ways that medicine cannot understand, Dr. Novella points out that this is often exaggerated.

Fact: Placebo Also Occurs Amongst dogs (and other animals)

Pharmaceutical companies employ the same double blind procedures on Dogs when testing K9 medication as they do for human medications. They use two groups—in this particular study all dogs with epilepsy—and give one group the medication and the other group a placebo. It turns out the Placebo phenomenon transcends the human/dog continuum because the placebo group reacted extremely positively to the drugs.It is often remarked that women have it easy because of their comparative ability to become inebriated with the help of less alcohol than men (hence the term ‘cheap date’. Well no more $100 ill-advised bender-induced bar tabs, because we can simply trick ourselves into thinking we are drunk. Researchers have found that those who believe they have been drinking vodka (which was actually simply tonic water and lime) had impaired judgment. They did worse on simple tests and their IQ became lower.Fact: Where You Live Affects Placebo

Americans tend to exhibit hypochondria more so than anyone else on earth, but who can blame us for the constant bombardment of medication advertisements on TV and in print? For some reason, we tend to assign a lot of power to drugs that can be injected into our veinsEuropeans, on the other hand, react more positively to placebo pills than injections. It would appear that cultural factors strongly influence the manner in which the placebo effect manifests itself. Placebo drugs used in a trial for treating ulcers worked much better in Germany than in Brazil. However, a trial testing for hypertension drugs found that Germany was the least reactive to the placebo pills. Fact: Placebo Still Works even Though You Know its A Placebo

The entire premise of the placebo effect is that patients who believe are they receiving real medicine are cured. But, it turns out that even when patients find out they are receiving a sham drug, it still functions effectively which makes absolutely no sense whatsoever.Fact: The Color Placebo Pill You Take Affects How Well It Works.

Researchers have learned that yellow placebo pills are the most effective at treating depression while red pills cause the patient to be more alert and awake. Green pills help ease anxiety while white pills soothe stomach issues such as ulcers. The more placebo pills have been taken the better, with those taken four times a day more effective than those taken twice daily. Pills that have a “brand name” stamped on them also work better than pills that have nothing written on them. It appears that we humans are superficial even when it comes to the fake drugs we ingest.Fact: Placebo Surgeries Are Also Effective In Curing Injuries, Somehow.

Results have shown that fake surgeries can be just as effective as the real thing, taking the placebo effect to the next level. The best part is obviously that fake surgery is way cheaper than real surgery.Fact: Placebo Effect Has Become More Powerful Over The Years.

Placebo effect was first noted in the late 1700s, but the true physiological implications weren’t really understood until the 1970s. Still, it seems that the more testing medical experts conduct, the more powerful the placebo effect has become over time. This is largely thought to be a result of our social conditioning; we place a lot of faith in medical professionals. As medical technology improves, mortality decreases and our faith in medicine becomes strongerThe placebo effect is a well-recognized phenomenon in human medicine; in contrast, little information exists on the effect of placebo administration in veterinary patients.HYPOTHESIS:

Nonpharmacologic therapeutic effects play a role in response rates identified in canine epilepsy trials.ANIMALS:

Thirty-four dogs with epilepsy.METHODS:

Meta-analysis of the 3 known prospective, placebo-controlled canine epilepsy trials. The number of seizures per week was compiled for each dog throughout their participation in the trial. Log-linear models were developed to evaluate seizure frequency during treatment and placebo relative to baseline.RESULTS:

Twenty-two of 28 (79%) dogs in the study that received placebo demonstrated a decrease in seizure frequency compared with baseline, and 8 (29%) could be considered responders, with a 50% or greater reduction in seizures. For the 3 trials evaluated, the average reduction in seizures during placebo administration relative to baseline was 26% (P = .0018), 29% (P = .17), and 46% (P = .01).CONCLUSIONS AND CLINICAL IMPORTANCE:

A positive response to placebo administration, manifesting as a decrease in seizure frequency, can be observed in epileptic dogs. This is of importance when evaluating open label studies in dogs that aim to assess efficacy of antiepileptic drugs, as the reported results might be overstated. Findings from this study highlight the need for more placebo-controlled trials in veterinary medicineEstimates of the placebo cure rate range from a low of 15 percent to a high of 72 percent. The longer the period of treatment and the larger the number of physician visits, the greater the placebo effect.The placebo effect is not restricted to subjective self-reports of pain, mood, or attitude. Physical changes are real. For example, studies on asthma patients show less constriction of the bronchial tubes in patients for whom a placebo drug works.Researchers have found, for example:

•Placebos follow the same dose-response curve as real medicines. Two pills give more relief than one, and a larger capsule is better than a smaller one.

•Placebo injections do more than placebo pills.

•Substances that actually treat one condition but are used as a placebo for another have a greater placebo effect that sugar pills.

•The greater the pain, the greater the placebo effect. It’s as if the more relief we desire, the more we attain.

•You don’t have to be sick for a placebo to work. Placebo stimulants, placebo tranquilizers, even placebo alcohol produce predictable effects in healthy subjects.As in all brain actions, the placebo effect is the product of chemical changes. Numerous studies have supported the conclusion that endorphins in the brain produce the placebo effect. In patients with chronic pain, for example, placebo responders were found to have higher concentrations of endorphins in their spinal fluid than placebo nonresponders.Use of prayer for healing

RESULTS We found that 35% of respondents used prayer for health concerns; 75% of these prayed for wellness, and 22% prayed for specific medical conditions. Of those praying for specific medical conditions, 69% found prayer very helpful. Factors independently associated with increased use of prayer (P<.05) included age older than 33 years (age 34-53 years: odds ratio [OR], 1.6 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.3-2.1]; age > or =54 years: OR, 1.5 [95% CI, 1.1-2.0]); female sex (OR, 1.4 [95% CI, 1.1-1.7]); education beyond high school (OR, 1.5 [95% CI, 1.2-1.8]); and having depression, chronic headaches, back and/or neck pain, digestive problems, or allergies. Only 11% of respondents using prayer discussed it with their physicians. CONCLUSIONS An estimated one third of adults used prayer for health concerns in 1998. Most respondents did not discuss prayer with their physicians. Prayer was used frequently for common medical conditions, and users reported high levels of perceived helpfulness.PURPOSE To describe the demographics, health-related and preventive-health behaviors, health status, and health care charges of adults who do and do not pray for health. DESIGN Cross-sectional survey with 1-year follow-up. SETTING A Minnesota health plan. SUBJECTS A stratified random sample of 5107 members age 40 and over with analysis based on 4404 survey respondents (86%). MEASURES Survey data included health risks, health practices, use of preventive health services, satisfaction with care, and use of alternative therapies. Health care charges were obtained from administrative data. RESULTS Overall, 47.2% of study subjects reported that they pray for health, and 90.3% of these believed prayer improved their health. After adjustment for demographics, those who pray had significantly less smoking and alcohol use and more preventive care visits, influenza immunizations, vegetable intake, satisfaction with care, and social support and were more likely to have a regular primary care provider. Rates of functional impairment, depressive symptoms, chronic diseases, and total health care charges were not related to prayer CONCLUSIONS Those who pray had more favorable health-related behaviors, preventive service use, and satisfaction with care. Discussion of prayer could help guide customization of clinical care. Research that examines the effect of prayer on health status should adjust for variables related both to use of prayer and to health status.

The research team conducted a randomized blinded trial of intercessory prayer added to normal cancer treatment with participants agreeing to complete quality of life (QOL) and spiritual well-being scales at baseline and 6 months later. The research team had shown previously that spiritual well-being is an important, unique domain in the assessment of QOL. Participants remained blinded to the randomization. Based on a previous study, the research team determined that the study required a sample of 1000 participants to detect small differences. Participants were patients at the cancer center between June 2003 and May 2008. Of 999 participants with mixed diagnoses who completed the baseline questionnaires, 66.6% provided follow-up. The average age was 61 years, and most participants were married/de facto (living with partners), were Australians or New Zealanders living in Australia, and were Christian. Intervention The research team asked an external group offering Christian intercessory prayer to add the study’s participants to their usual prayer lists. They received details about the participants, but this information was not sufficient to identify them. Outcome Measures The research team used the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-being questionnaire to assess spiritual wellbeing and QOL. Results The intervention group showed significantly greater improvements over time for the primary endpoint of spiritual well-being as compared to the control group (P = .03, partial η2 = .01). The study found a similar result for emotional well-being (P = .04, partial η2 = .01) and functional well-being (P = .06, partial η2 = .01).CONCLUSIONS:

Participants with cancer whom the research team randomly allocated to the experimental group to receive remote intercessory prayer showed small but significant improvements in spiritual well-being.

- For many years, the placebo effect was considered to be a nuisance effect that needed to be controlled in clinical trials,” Dr. Novella stated. “More recently, the placebo effect has been redefined as the key to understanding the healing that arises from the medical ritual in the context of the patient \ provider relationship and the power of imagination, trust and hope.” Should medical doctors rely on deception to avoid using potentially more dangerous medications? And how effective or reliable is the placebo effect anyway? Dr. Novella pointed out that advocates of alternative medicine have begun using the placebo effect as a way of marketing their products by stressing that the mind can heal the body in way that medical science cannot understand. The more expensive the placebo, the longer the placebo effect lasts for patients. Color of the pill can be important too. For whatever reason, blue sleeping pills are more likely to benefit patients than pills of another color. Medications to reduce pain are often sold in red pills or capsules since marketing studies showed these to be more effective, etc. Patients who take placebos regularly do better than patients who are not compliant with their treatment, regardless of the fact that placebos have no real health benefit. When placebo medications are hard to obtain, more expensive, or otherwise stressed to be valuable to the patient, the placebo effect becomes even stronger. “Physicians are very much aware of the fact that we examine patients, we touch them, and that in and of itself has a physical effect,” Dr. Novella continued. “Being touched in a safe context relaxes and reassures the patient.” There are also non-specific effects in making patients the center of attention. Bringing them into the doctor’s office and asking questions about their symptoms can make them feel as if they are part of the medical team dealing with the health problem. Different non-specific effects can all contribute to what is regarded as the placebo effect. For “fuzzy” symptoms such as chronic pain, patients are often able to convince themselves that placebos are as effective as actual pain medications. Although the human body continues actual physiological mechanisms to control pain, such as generating endorphins, this is not as reliable as actual pain medication. Intriguingly, Dr. Novella also described a recent study showing that people with high dopamine levels in the brain are more likely to experience placebo effects. Although this result only applies to pain and has still not been replicated, the study does suggest that there is a genetic factor that might be at work with the placebo effect And the placebo effect varies from disease to disease. Since subjective ratings of pain, depression, or any other symptom being measured cannot be directly compared. It also means that the placebo effect cannot be linked to any particular physical process at work in the body. Most diseases where a placebo effect has been observed, such as pain, asthma, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), are also especially vulnerable to psychological factors like stress and anxiety. But even when psychological effects are taken into consideration, the evidence that the placebo effect is actually working seems limited. Whatever relief the placebo provides is usually short-lived and the benefit is purely psychological, not physiological. There is also the ethical question surrounding placebos. Are medical doctors ethically permitted to deceive patients into believing they are receiving actual treatment instead of a placebo? Even if the medical doctor believes that the patient will benefit? Actually, Dr. Novella argues that deception is not always necessary and some placebo studies with IBS patients showed that placebo effects still relieved symptoms even when the patient knew about the placebo (though this result is controversial). The real controversy surrounding placebos deals with what the placebo effect actually is and what yjis means about the human capacity for self-healing. While alternative medicine advocates use the placebo effect as evidence that the brain has the ability to heal physical illness in ways that medicine cannot understand, Dr. Novella points out that this is often exaggerated.

Related: